ABC: what are nature-based solutions and how can they help solve the climate crisis?

The role of nature-based solutions in carbon removal

These days, there’s quite a bit of talk about nature-based solutions to climate change (sometimes also referred to as natural climate solutions). They got top billing in the newest IPCC report on climate change and could deliver as much as 5 gigatonnes (that’s 5 billion tonnes!) of CO2 removal & reduction by 2030.

Nature-based solutions are actions that help to restore natural ecosystems and address, but also adapt us to, climate change. These solutions are developed in collaboration with natural systems as opposed to technological ones. Keep reading to find out more about the difference and the impact of these two solutions.

But first, how much CO2 do we need to remove?

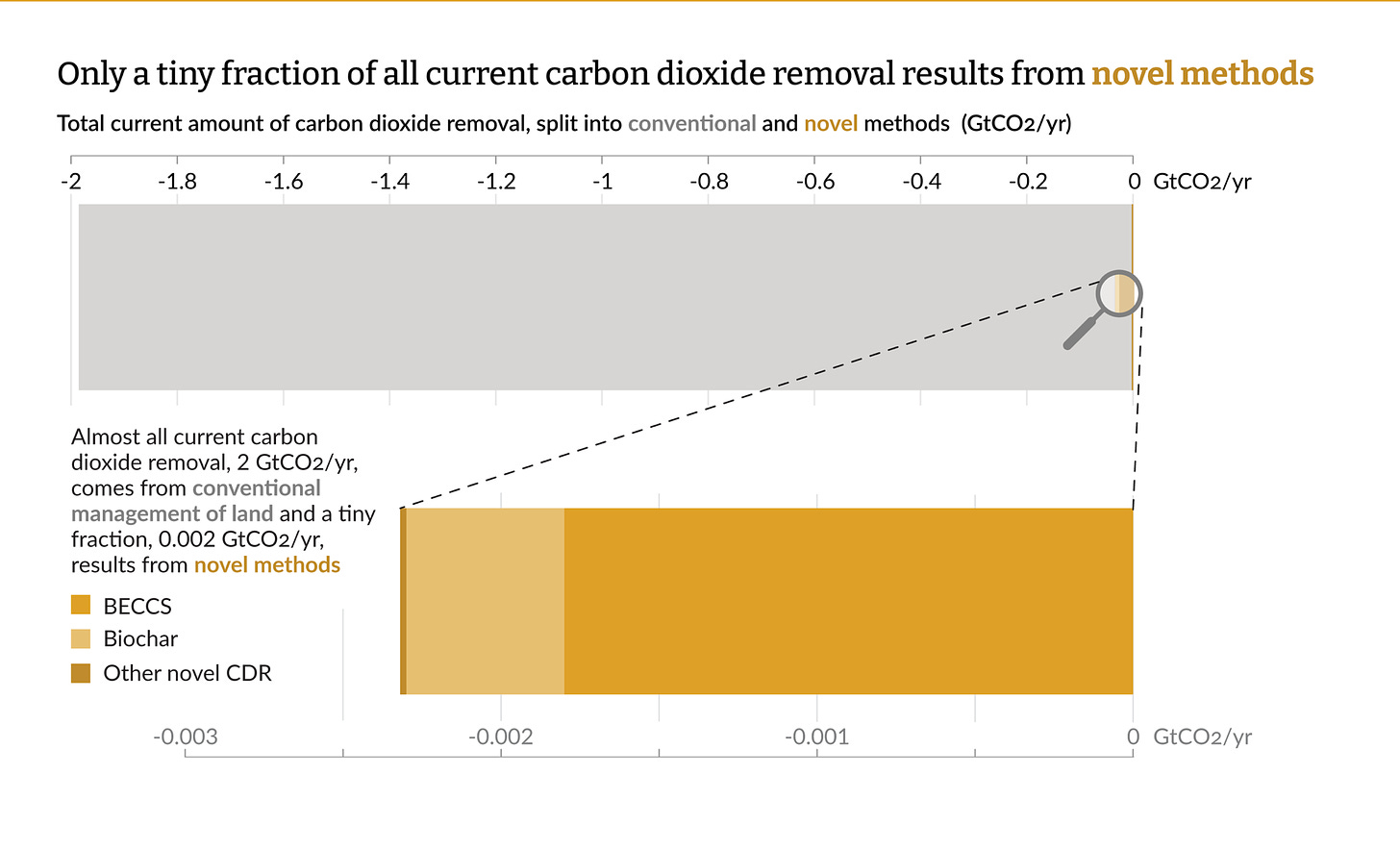

For context, the rough annual estimate for carbon emissions is around 50 gigatonnes. How much of this are we currently removing? Around 2 gigatonnes. Here’s a visualisation of the challenge:

What CO2 removal methods account for the 2Gt of current removals?

A recent study by scientists at the University of Oxford found that 99.99% of current CO2 removals come from nature and land management (you can access this report directly on stateofcdr.org).

This category includes, among others:

afforestation

reforestation

soil carbon

peatlands

agroforestry

durable harvested wood products (e.g. buildings, furniture)

etc

Many of these use the same natural principle: trees or other plants capture CO2 and convert it to carbon (which they store in branches and roots), releasing the oxygen back into the atmosphere. Another way to think about it: trees are a type of direct air capture technology, fine-tuned by 370 million years of evolution.

Yeah, so nature is doing most of the carbon removal today… But the future is all about direct air capture, right?

Well, that is a beautiful hope. It is unfortunately also not super likely. Let’s talk it through.

Direct air capture (known as DAC for short) is a type of technology that removes CO2 from the atmosphere. When combined with long-term carbon storage (e.g. injecting CO2 underground where it will mineralise), it is undoubtedly the best tool we have for solving the climate challenge. If we could just scale DAC to 50 gigatonnes tomorrow, we would not be facing planetary-scale challenges.

What’s stopping us from scaling DAC?

Firstly, DAC is currently done on a very tiny scale. In 2021, the total operating capacity of DAC plants around the world was around 11 300 tonnes of removal. That’s roughly 0.000005% of the total annual removals we discussed above. To reach 1 gigatonne of removals (about half of what nature is currently contributing), DAC will have to grow ~88 500x.

Of course, every technology is small when it starts off, and we would expect DAC to scale very fast. In the technology world, annual growth rates in excess of 100% are not unheard of, and even 1000% has happened before. However, DAC is not a purely software problem - it requires building real-life factories. Scaling construction 88 500x is a lot harder than scaling a software solution.

The second challenge with scaling DAC is that it requires large amounts of energy. Why? Because CO2 in the atmosphere is still highly diluted. At the time of writing, the most up-to-date CO2 concentration from CO2.earth was 419.26 ppm. That is equivalent to 0.04% of the atmosphere. To visualise what it’s like to try to distil that, imagine you had 2500 needles, and needed to find just 1 in the pile.

This means that DAC is quite energy-heavy - extracting CO2 requires compressing air, which in turn requires a lot of energy. This means it is best suited for countries with abundant, excess fossil-fuel-free energy. In the next two decades, the world is more likely to face an energy shortage of 3-5% by 2030, rather than an energy excess. And the while the energy mix has to yet been decarbonised (i.e. there are still fossil fuel sources contributing energy to the grid), using “green” energy for DAC rather than to replace existing fossil fuels probably doesn’t make sense in net CO2 terms.

Those two reasons mean that while DAC is important and necessary, it cannot alone significantly increase the current 2 gigatonnes of CO2 removal annually.

This brings us back to nature-based solutions (NbS for short).

So… back to nature. How much carbon removal and avoidance could nature-based solutions account for?

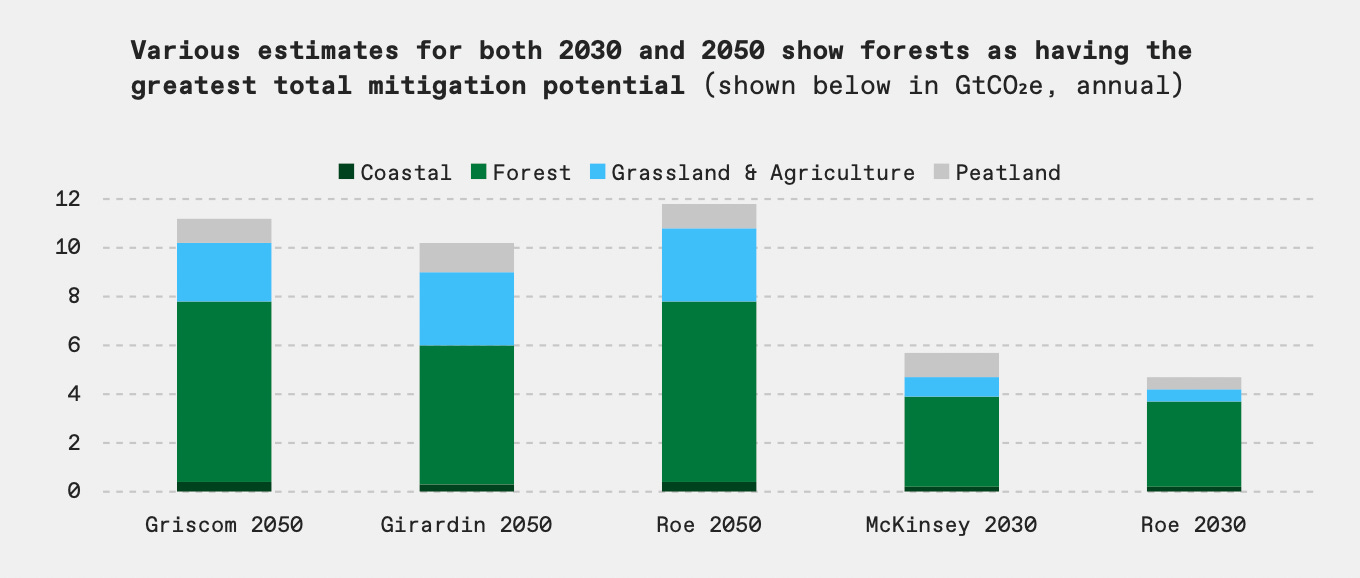

There are a range of studies exploring the annual CO2 potential of nature-based solutions. Thankfully, the UN’s Environment Programme looked at a range of studies (full report here) and combined them in one graph (reproduced below) so that we can look at the ranges. For 2030, the expected range is 4.5Gt - 5.75Gt; by 2050, the range 10-12Gt. In all cases, these are annual removals/avoidance - so could be compared to the 50Gt of CO2 we are collectively emitting each year.

What would it take to unlock this increased carbon removal through nature?

Unlocking increased carbon removal through nature can be done via different paths. Some examples:

Afforestation - turning unused or underused land into forests can significantly increase the amount of carbon that land can store.

Improved forest management (Impact forestry)- implementing technology-driven forest management practices can enhance carbon sequestration in existing forests. This might include changing harvest type or -frequency, or planting new saplings in between a more mature forest.

Soil carbon in agriculture - practices like agroforestry and cover cropping can increase carbon sequestration in agricultural soils.

Peatland and wetland restoration - drained peatlands/wetlands are likely emitting a large amount of CO2 from the soil. Rewetting/restoring these ecosystems can help stop those emissions and help these lands start sequestering more carbon.

By combining technology, policy support, public engagement, and scientific advancements, we can unlock the full potential of nature-based solutions to remove carbon from the atmosphere and combat the climate crisis effectively.

Surely, there are also issues with nature-based solutions? What are some downsides?

As with any climate tool, nature-based solutions come with challenges. Some of the key ones often mentioned are:

Time required to reach full potential - trees and plants grow slowly. Peat accrues even more slowly. As a result, if we want to see significant carbon storage in nature-based solutions

Vulnerable to climate change impact - climate change brings increasing temperatures, which in turn can cause forest fires & a wider spread of pests like bark beetle

Land use competition with other uses - there is a limited amount of land available, and using it for NbS might mean land not available for other uses required (such as housing, or growing food)

These are all valid questions! But they can be mitigated in the following ways:

Planting early and often

The time to scale nature-based solutions is now. In order for these to start storing significant amounts of CO2 between 2030 and 2050, we need to be actively planting/changing management practices/rewetting peatlands etc today.

Taking the warming climate into consideration in planting and management plans

It’s true that the trees that thrived over the last 100 years may not be the same ones that thrive in the next 100, and that a drier climate may require different management. Luckily, we have both the scientific knowledge required (in the form of research into drought-resistant plants etc) and the new management and monitoring technologies to reduce risks. For example, remote sensing can identify pest loss much earlier, allowing its spread to be curtailed.

Data-based, rigorous analysis of land suitability

We know that not all land is suitable for use in nature-based climate mitigation. With modern data-based tools, we can make sure we’re not damaging valuable food growing areas or biodiversity-rich natural ecosystems.

Example from Arbonics’ land analysis tool, which takes into account over 50 factors when considering the suitability / unsuitability of afforestable land